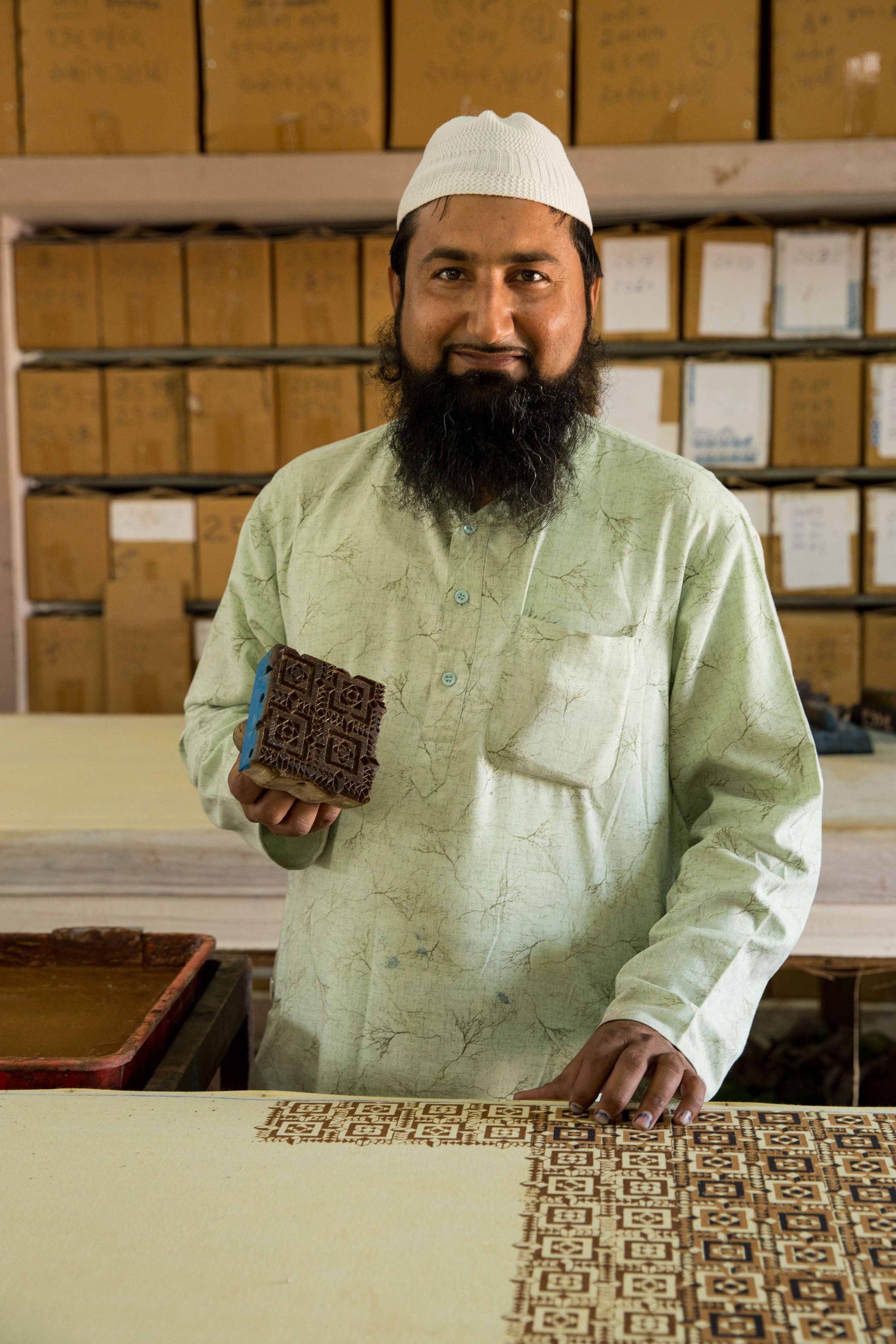

Sufiyan Ismail Khatri

Reviving a Sense of Reverence for the Ajrakh Tradition

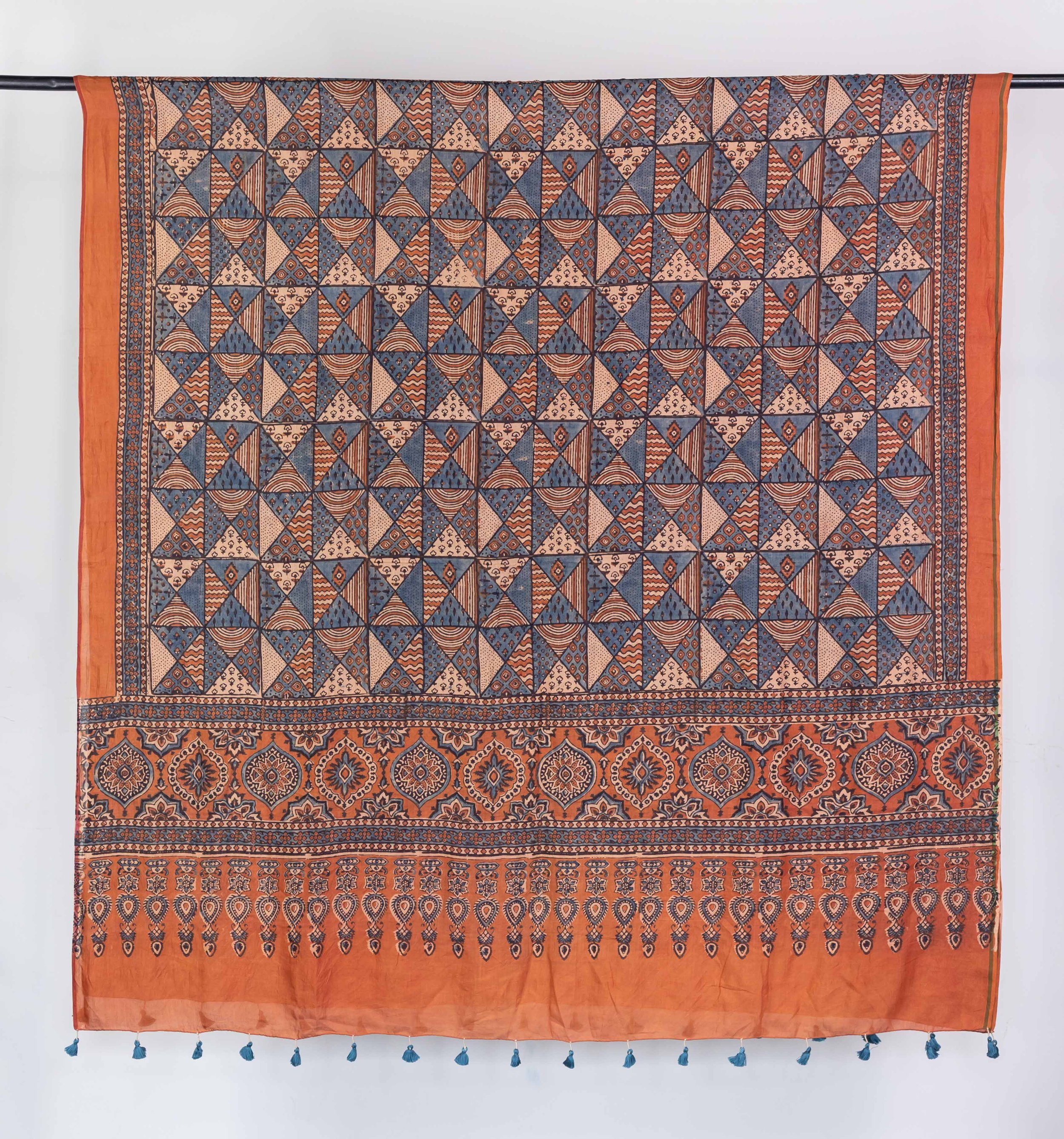

When Sufiyan Ismail Khatri creates his rich textiles, he is continuing the four thousand year old tradition of Ajrakh hand-block printing, a tradition that goes back to the early civilizations of the Indus Valley. Khatri’s collection includes rugs, wall hanging, pillows, and household items all adorned in perfectly symmetrical Ajrakh designs, an homage to unity and order. A part of the Khatri Community of Kutch, Gujarat, Sufiyan shares his desire to re-instill a sense of reverence for the craft of Ajrakh and the artisans who are committed to this technique.

While Khatri’s work looks effortless, this process is no easy feat. An Ajrakh textile goes through a multi-step process of washing, printing, dyeing, and boiling. The first step always begins with hand carving the block from teak wood, artisans who follow the Ajrahk technique use complex mathematical calculation and artistic abstraction to create vegetal and geometric patterns that will produce an infinite design. Typically the washed fabric is first dyed in myrobalan (bark of Indian gooseberry), in order to loosen the fabric’s pores. It is then block printed with a paste of lime, gum-arabica and clay, any portion of the fabric that comes in contact with this paste will resist any dye color or mordant. This method of resisting the fabrics with clay is very unique to the craft of Ajrakh. Artisans will then print their textile with iron, for black tones, indigo for blues, or mordants combined with plant dyes like madder, pomegranate skin, turmeric, henna, lac, logwood, sappan wood etc. For textiles that require two-sided prints, the process is repeated. Fabrics then must be washed, dried in the sun before being sent to women artisans in neighboring villages who hand-finish the textiles with tassels, fringes, etc.

Ajrakh designs are not purely ornamental, they carry great cultural importance and are reflective of the region’s landscape. Some recognizable motifs include the 8-pointed star, champa kali (a local shrub), badam-bhutta (almond-shaped), patterns of night skies, ray-shaped florals and rosettes, riyal (Saudi currency), taaviz, kan-karak (dates), mifudi (rain-drops), koyaro (spider-web), jaalis (window-screens), mihrabs (minarets), and garden designs. Traditionally, the nomadic Maldhari Muslims were primary purchasers of Ajrakh who traveled in the desert belt of KutchSindh. They wore Ajrakh printed turbans and sarongs in distinct black, crimson-red and Indigo colored patterns.

Khatri shares that prior to the 1950’s, craftsmen took pride in their creations as they were supported by the local community. With the introduction of the global market and industrialized practices, much of this reverence has been lost. “The craft brought to the community an identity and a standing in the society. I want to bring back that straightforwardness to the craft again in modern contexts.”